A Sifu Who Holds Nothing Back!

Posted By : KorElement

Date: Oct 19, 2011

Master Terence Yip believes wing chun should lift its shroud of secrecy and be taught openly to all people.

By Andrew Bell

Wing chun, a southern style of Chinese kung-fu, is a realistic and effective method of self-defense. Its practitioners develop an ability to sense and neutralize or redirect an opponent's attack with an economy of movement. There are probably as many ways to teach wing chun as there are sifu.

Many readers are probably familiar with the six forms and the sensitivity exercises of chi sao ("sticky hands") and chi gerk ("sticky legs") of wing chun. There are three empty-hand forms (siu nim tao, chum kiu, and biu tze), one wooden dummy form, and two weapons forms (the long pole and the butterfly knives). Along the way the student is taught, and eventually refines, his chi sao and chi gerk practice. This is the standard progression one must move through to complete the system. Yet within this progression, how is the student taught? What is the methodology of the sifu?

Many wing chun sifu teach in a traditional manner. Chinese kung-fu has a history of being taught in secret. This is in contrast to the way other martial arts, such as karate and tae kwon do, have been taught in the U.S. This difference in the teaching methods between Chinese martial arts on the one hand, and Korean and Japanese martial arts on the other hand, is due partly to cultural differences and partly to differences with how the respective arts came to America.

Karate and tae kwon do were originally popularized in the U.S. by American teachers. In the book, In Search of the Ultimate Martial Art, author Dr. Jerry Beasley says, "The art of karate was introduced to the United States by former World War II servicemen who had trained in the arts while stationed in the Orient. Robert Trias is said to have been the first American to open a school in the U.S. in 1946."

Carrying On The Tradition

This had a major impact on karate and tae kwon do in America. First, since many pioneer teachers were ex-soldiers, it was natural for them to carry on with the hierarchal structure of the colored belts and the dan system. Secondly, they taught as they learned, openly, with clear expectations and instruction. There was no talk of "mysterious" death-touch strikes, and the like. The instructors wanted to teach and the students wanted to learn. Finally, because the arts were taught out in the open, it was easy to standardize a curriculum to be copied and spread. Karate and tae kwon do schools and tournaments flourished. Today it's a rare town in the U.S. that doesn't have a dojo or dojang nearby.

Kung-fu, on the other hand, was originally brought to the U.S. by Chinese and was taught exclusively to other Chinese. Bruce Lee received a lot of grief in the early '60s when he taught kung fu to non-Chinese.

One reason why kung-fu was kept "secret" was due to tradition and culture. To a large extent, many kung-fu styles literally did not go out of the family; they were passed on from father to son. In fact, wing chun was very much a secret style until Yip Man brought it out.

An example from Chinese medicine can help to illustrate this "tendency to secrecy" of Chinese culture, especially since many Chinese kung-fu sifu have traditionally also been herbalists and acupuncturists. Historically in China, herbal prescription formulas have often been family secrets passed from one generation to the next. In this way, a famous and respected doctor could guarantee employment for his children.

This certainly provided for the financial security of a few Chinese families, but was it good for Chinese medicine? China's medicine in the 17th and 18th centuries was comparatively advanced to Western medicine in Europe and America. In the West, the sick had their veins cut open to make them bleed so they could "clean" their system. Howard Haggard says in the book, The Doctor in History, "...in the eighteenth century (bleeding) was one of the commonest practices in (Western) medicine. It has been said that George Washington was bled to death by his physician, Dr. Crait, who treated him in his last illness."

Keeping Out The Chinese

Meanwhile, in China, the system of acupuncture points and much of their herbal materia medica were already highly advanced. Today, of course, Western medicine has progressed tremendously while Chinese medicine, by comparison, has not. How much further could Chinese medicine have advanced if doctors had shared their knowledge with each other?

Another factor which contributed to this attitude of secrecy about kung-fu in the U.S., of course, was racism. Even as recently as 25 years ago, Bruce Lee was passed over for David Carradine in the role of Caine in the "Kung Fu" TV series because Hollywood executives didn't think America was ready for an Asian superstar. The success soon afterward, however, of Enter the Dragon certainly proved them wrong. In any case, the Chinese have the dubious honor of being one of a select few groups which have been prohibited from immigrating to the U.S. In her book, Chinatown: Portrait of a Closed Society, author Gwen Kinkead says, "The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 barred Chinese laborers or their wives from entering the U.S. It excluded Chinese from most occupations...It also forbade them from becoming citizens. President Grover Cleveland supported the act, declaring the Chinese 'an element ignorant of our constitution and laws, impossible of assimilation with our people, and dangerous to our peace and welfare'." The Act was finally repealed at the end of World War II.

Viewed from this context, it is certainly understandable, historically, to see why the Chinese were reluctant to teach kung-fu to non-Chinese in America. However, the question needs to be asked: Is the situation in America the same today? Because of the pioneering efforts of Bruce Lee and Ark Wong to teach kung-fu to all people in the early '60s, and especially because of the movies of Bruce Lee, many people in America and all over the world have great respect for Chinese culture and kung-fu. Is secrecy really the best way for kung-fu to develop and grow in the U.S.?

Since the passing of both Yip Man and Bruce Lee in the early 1970s, wing chun have become the single most-popular style of kung-fu. The style is growing by leaps and bounds, yet "pure" wing chun is in jeopardy of not surviving. There are two primary reasons for this. First, some prominent sifu have changed original wing chun techniques to bolster their claims of having learned "secrets", while others have altered techniques in failed, misguided attempts to "improve" the art. Secondly, many sifu are teaching bad kung-fu. They are doing this either because they themselves never learned correctly or because they try to "hold back" some of the kung-fu from the students.

A Fighting Art Is Born

It is now part of wing chun legend that the Shaolin nun, Ng Mui, who is the founder (sijo) of the style, was able to teach Yim Wang Chun how to be an effective wing chun fighter in a year. The story continues that Yim Wing Chun, a woman, was then able to defeat a much-larger man. So why is it today that after six months many wing chun students have only learned the first form, siu nim tao? Why is it that many have barely begun chi sao after one year?

How long will it be before pure wing chun is completely overtaken and relegated to being just a distant memory, all but forgotten? If wing chun is to survive in its original, unadulterated form, it has to be taught openly, correctly, and as Ng Mui intended, quickly.

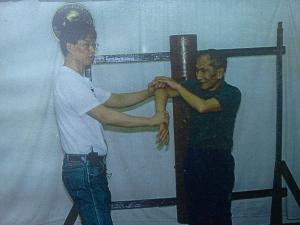

Master Terence Yip (Yip Pui) does just that in New York City where he teaches. He studied and mastered the complete wing chun system in Hong Kong with grandmaster Yip Chun and is Yip Chun's most-senior student teaching in the United States. Yip Chen is the eldest son of Yip Man (Bruce Lee's teacher), who brought wing chun out from behind "the bamboo curtain" in China to Hong Kong.

In the first year alone with Yip Chun, Terence Yip was able to learn siu nim tao, chum kiu, biu tze, and the wooden dummy! Many of master Terence Yip's students in New York City do the same and are able to complete the entire system within two-to-three years. How is this possible?

Open-Door Policy

First, with master Yip, there are no secret "forms" or "techniques." Everything is taught openly to all students. All students have an equal opportunity to learn to the best of their ability. Nothing at all is "held back" from the students. Secondly, master Yip has attempted to improve the organization and systemization of the curriculum by borrowing an idea from karate and tae kwon do. He has instituted a system of ranking accompanied by colored sashes. This serves a dual purpose to motivate students and to lay out clearly what each student is expected to know at each level. It facilitates bringing wing chun out into the open. This, it is hoped, will aid in the growth, development, and spread of true wing chun in the U.S.

Thirdly, master Yip begins teaching shifting very early. Properly shifting on both heels is so difficult so master that is takes time. In the original wing chun curriculum, students do no shifting in siu nim tao. It is only in chum kiu, the second form, where students begin to shift with simple techniques. In the third form, biu tze, and in the wooden dummy form, students shift with more complicated techniques. Of course, throughout this process, students should be trying to integrate shifting into their chi sao practice.

Master Yip takes this process a step further. He teaches students how to shift beginning on day one in the class. They do simple shifting on their heels without hand techniques. Soon after, they learn other simple techniques to add to their shifting, such as the basic two-person lop sau exercise but with shifting.

Finally, Master Yip accelerates the students' progress through the "drills" component of the class. This happens in two ways. First, students do individual traps and defenses in isolation separately from chi sao. Chi sao is like a free-flowing laboratory where students try to apply what they have learned with a partner. The drills allow students to work and rework combinations, so they can be executed more effectively in both chi sao and in fighting. In addition, master Yip has taken several movements from the wooden dummy form and teaches them as drills with or without a partner. This is a great idea. Some movements require a lot of coordination and practice to master. By teaching some movements before the student learns the dummy, the student has that much more time to work on them. The result can be shaving a year or more off the time a student needs to learn.

Master Yip believes wing chun can and should be improved. However, unlike many other sifu, he has not altered the techniques. Master Terence Yip believes wing chun needs to be brought to the public the way it was meant to be taught by Ng Mui: correctly and quickly. He just feels the art should be removed from the shroud of secrecy that has surrounded it and be taught out in the open, equally to all students.

Master Terence Yip can be contacted at, Yip Pui Martial Arts, P.O.box 230388, Brooklyn, NY 11223; (718) 265-3234.

Other articles by sifu